This is a guest post by Abdulhafeez Babatunde Siyanbola, currently a doctoral student in the Department of Industrial Design (Graphic Design Section), Ahmadu Bello University in Nigeria. He is a brand consultant, graphics designer, photography enthusiast and the Creative Director of Craftsentials (an e-commerce site).

Nigeria’s Railways

The invention of the rail transport system redefined the movement of people and goods across the globe. It is convenient, safe and cheap. Railways enable seamless transportation that engender robust economies, anchored on human resources and services accessible with limited regulatory intervention by government or its bodies.

The rail transport system creates jobs and enhances the growth and development of cities. Employments are created through the building of tracks, furniture foundries, coaches and others. Agricultural produce, clothing, animals, petroleum products and equipment can easily be transported across countries with the railway system.

Rail transport had immense impacts on the Industrial Revolution in Europe and America and it was a viable alternative to steamboats that were employed for traveling through canals and rivers. ElMammann (n.d) posited that the engine behind the industrial revolution of the 19thcentury were the railways and an efficient railway systems and not democracy because, democracy was already in place in most of the industrializing nations of the time.

According to Osuji (2013), before the development of modern highways and airports in Nigeria, railway was the only means to travel efficiently and move goods from one point to another. This created the leeway for the modest development witnessed from the colonial times and before the early 1970s.

Olakitan (2015) describes the earlier public perception of the railways and the influence of modernisation on this system, that

the thought of trains might bring the picture of an old steam-engine huffing and puffing up a mountain into mind. Modern trains are nothing like they used to be 200 years ago. Trains can go 20-30 times faster than the first steam engine did, like France’s TGV train that can hit 300 miles per hour, this is faster than traveling in a racing car. Trains have evolved and grown as convenient subway transportations that many people take every single day.

Pre-independence

Historically, the railways in Nigeria were conceived and constructed from Lagos to the furthermost parts of Northeastern part of the country, to open up the hinterland of southwestern Nigeria along its corridor.

In 1896 railway construction began from the Iddo area with extensions made along the Lagos route with stops at Ota, Ifo, Arigbajo, Papalanto, Abeokuta and Ibadan in 1901 (Nigerian wiki, 2008). But due to limited finance the further development of the railway in Southern Nigeria was delayed. Proposals linking Benin, Sapele in 1906 and Ibadan with Oyo in 1907 came to nothing.

Records have it that the Lagos railway terminal at Iddo was constructed to connect Lagos Island with Lagos mainland and act as a transit stop for trains using the railroad bridge constructed along two major road networks that connect the Island with other parts of Lagos; the Carter bridge and the Denton bridge.

However, in 1904, the colonialists decided to construct the rail road linking Ibadan with Osogbo and Ilorin in 1907; it was approved to begin construction from Ilorin to Jebba (Osuji, 2013).

Osuji (ibid) narrates how Baro-Kano rail route was developed

The Baro-Kano line was predicated on developing the trade routes along River Niger. The initial intention was to develop a rail line along the Niger River and Port of Forcados in Southern Nigeria, and importantly both routes leading to Kano. In September, 1907 the British government approved a credit of £2million for a railroad from Baro to Kano. Reason for this, was the cutting of expenses and enhancing communication between areas of interest, which with time would cut the time and cost of transporting troops from one garrison to another and ease associated with transporting goods across the North.

Also, it was acknowledged that the British Cotton Growing Association had interest in seeing a railroad to the cotton growing areas in Northern Nigeria. The rail road would go from Baro to Bida, Zungeru and Zaria to Kano and was started in 1907, with a completion target of four years (Nigerian wiki, ibid). The railroad was a narrow-gauge, single track with a speed of 12 miles per hour and was completed in 1911. In the same year, a rail line linking Apapa to Ebutte Metta in Lagos was built and in 1912 another linking Jebba with Minna along the Lagos railway followed.

In 1912, a light rail from Zaria reaching Bauchi was built; further extensions were made along the Bauchi light rail, linking the system with the tin producing fields in Jos and Bukuru. Subsequently preparations began for the development of another railway trunk from the Eastern region of Nigeria to the North-east region. A deep water port site along the Bonny River was chosen in an area of now Port Harcourt as location for the terminal. The new trunk was built to benefit major economic activities such as the Udi coalfields and upper Benue regions (Osuji, ibid).

In the 1920s and early 1930s, extensions such as the Zaria-Gusau-Kaura Namoda (1929) were built. Two other extensions, Ifo- Idogo and the Kano-Nguru lines were made in 1930. For 31 years, from 1927 to 1958, there was no railway development. It was the construction of Kafanchan-Bauchi rail line (238km) from 1958 to 1961 and the Bauchi-Maiduguri line (302km) in 1961–1964 that brought the total rail route of the Nigerian railway network to 3,505km (Bisiriyu, 2016).

There were plans to extend the existing rail tracks which were never implemented, some of these proposed extensions were captured by Okeyode and Yakubu (2015) that

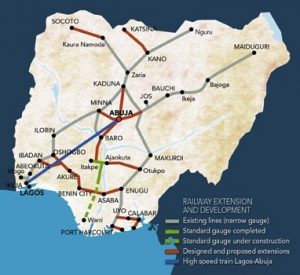

There are a few extensions of the 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) gauge network planned, but none of these have ever materialized since 1980, from Gusau on the branch to Kaura Namoda to Sokoto, 215 kilometers (134 mi), from Kano to Katsina, 175 kilometers (109mi), and from Lagos to Asaba. In the centre of the country a 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) gauge (standard gauge) network is very slowly progressing, its main line extends over 217 kilometers (135 mi) from Otukpo to the Ajaokuta steelwork. A further 51.2 kilometers (31.8 mi) line of standard gauge is operational between the Itakpo mines and the Ajaokuta steelworks. There are plans to add more standard gauge lines to these ones: Ajaokuta to Abuja and Ajaokuta to the Port of Warri, together 500 kilometers (310 mi) and from Port Harcourt to Makurdi over a distance of 463 kilometers (288 mi).

Post-Independence

Act establishing the railway system was enacted by the parliament in January 1955 and the railway became a statutory corporation known as Nigerian Government Railway (Ikechukwu, 2014; Okeyode & Yakubu, 2015). Ilukwe (1985) notes that this Act was followed by the ‘Nigerianization’ of the corporation in 1960 after the attainment of independence.

With the incorporation of the Nigerian Railway by the Act of 1955, and as amended by act No. 20 of 1955, it became a corporate body with perpetual succession and a common seal with power to sue and be sued in its corporate name, and to acquire, hold and dispose of movable and immovable property for the purpose of its function under the Act (Ikechukwu, ibid). The general objectives of the corporation are summarized as follows (Nigerian Railway Corporation, 1990):

- Carriage of passengers and goods in a manner that will offer customers full value for their money;

- Meet costs of operations;

- Improve market share and quality of service.

- Ensure safety of operations and maximum efficiency, and

- Meet social responsibility.

In 1978, the Obasanjo government through the Nigeria Ministry of Transport engaged the services of an Indian group: Rail India Technical and Economic Services to operate the railways. Bisiriyu (2016) noted that the Indian experts met only 20 functional locomotive engines in the system. By the time they were leaving in the early 1980s, the number had increased to 173. According to Nigerian wiki (ibid), this period also coincided with large capital outlays from the government to the railway sector, though a large amount of the money was diverted to an ill-fated change to standard gauge. The contract resulted in modest positive changes but the contract was not renewed.

By the end of the 1980s, reduced funding from the government, import bans and managerial problems decreased the performance of the railways. Osuji (ibid) highlights that an investigation carried out by the National Mirror shows that Nigeria currently has only 3,505 kms of narrow gauge and 276kms of standard gauge that will connect Ajaokuta with Warri.

The network of rail tracks comprises of the following lines:

- Lagos – Agege – Ifo – Ibadan – Ilorin – Minna – Kaduna – Zaria – Kano, 1,126 kilometers (700 mi)

- Ifo – Ilaro, 20 kilometers (12 mi)

- Minna – Baro, 155 kilometers (96 mi)

- Zaria – Kaura Namoda, 245 kilometers (152 mi)

- Kano – Nguru

- Kaduna – Kafanchan – Kuru – Bauchi – Maiduguri, 885 kilometers (550 mi)

- Kuru – Jos, 55 kilometers (34 mi)

- Kafanchan – Makurdi – Enugu – Port Harcourt, 737 kilometers (458 mi)

- Port Harcourt – Onne – gauge convertible sleepers

The facts, opinions, views or positions expressed or established in guest posts represent that of their writers and not necessarily of www.edusounds.com.ng.

Please, leave your thoughts on this post in the comment section and feel free to share the article with your contacts. Thanks for taking out of your precious time to read my article/s!

If you like this post, kindly subscribe and/or follow me on Twitter @otukogbe and @EdusoundsNg or on Facebook at edusoundsng.